It’s not photography that’s in danger, it’s truth.

Just a little PSA in case you missed it. Last week I shared a link to buy the printed-on-paper version of Art + Math. You bought them, which I appreciate! We still have more for sale and I’d love for more of you to acquire them. If you’re looking for the perfect gift for that special someone in your life (me), hit up the A+M store for the lowdown on this quaint little collection of essays. Now, on with the show.

Throughout October, if the television in my house is on, it’s on scary stuff. Last night it was the newest installment of the Netflix series “Monster,” which is about the real life serial killer who inspired the movie “Psycho.” Ed Gein was his name, and he was not very nice at all.

As I often do when watching fictional stories about real people, I opened my laptop and navigated to Google Maps to get a better look at the place where it all happened. Having oriented myself to the town of Plainfield, Wisconsin, I typed into the search bar “Ed Gein…” and watched it autofill “…house site.” I’m not the only weirdo who does this, clearly.

Google took me to an aerial view of the intersection of 2nd and Archer, where the Gein family homestead sat well outside of town. An ideal place to get away with terrible things.

Google Maps might be my favorite website. It’s one of my most visited, certainly, and the one that’s most practically helpful on a day to day basis. It’s the perfect intersection between my online and offline lives. I use it to scout possible production locations or determine which facade of a structure faces the sunrise. And of course I use it to find places to eat, sleep and gas up the car. Mostly, though, I use Google Maps to find the fastest route to some place I’m supposed to be. It’s one of the most practically useful websites around.

Unless, of course, Google continues to “improve” it by replacing a lot of actual human intelligence with the artificial kind.

Earlier this week I stumbled upon a great discussion about all the ways Google’s search function was becoming less capable at the hands of AI. Mainly it was people complaining about how good it used to be and how bad it is now.

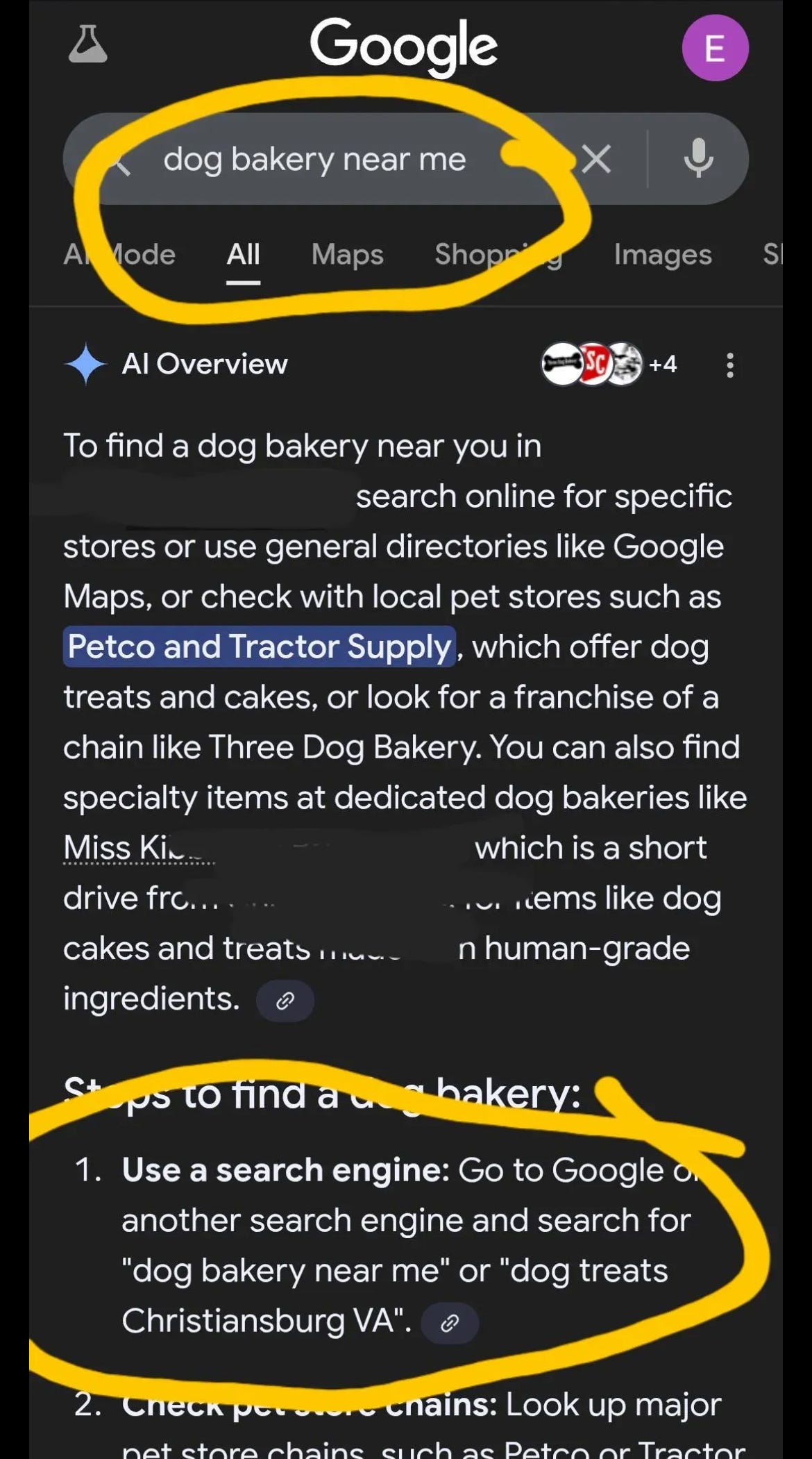

My favorite item in the discussion was a screenshot of someone’s search for a “dog bakery near me.” Google’s AI Overview helpfully suggested that, to find a dog bakery nearby, simply search online for stores or general directories: “Step 1: Use a search engine.” Oh the delicious irony. Not since “add glue to your pizza sauce” has an AI foible brought me so much schadenfreude.

I’m not an AI hater, I swear. But I am increasingly skeptical. It’s because my hit rate with the technology is simply not very good. Yes, it absolutely can do some very impressive things. But ruining things that already worked really well — search results, art, poetry — is not engendering confidence.

Watching a behemoth like Google, with its $3 trillion market cap, work so hard to shoehorn half-baked technology into what was previously a pretty amazing offering, shows they are willing to compromise the effectiveness of their core business just to, what, to be AI?

I’m no genius tech bro, but it seems like serving subpar results could have the opposite of its intended effect. Instead of impressing us with AI’s effectiveness, it’s pretty frequently stupefying us with its awkwardness. I keep being told how game-changing LLMs are — or how they’re going to be any minute now — and so I keep testing them out. Nine times out of ten I end up with terrible results. Fast, but terrible.

I’m pretty comfortable saying that if your thing is formulaic, AI is going to take over. Trouble is, the most interesting stuff isn’t very formulaic. And lots of things in the creative world that may seem formulaic are not. Their human imperfectness is often what makes them interesting.

LLMs are often more concerned with appearing helpful than actually being helpful. There are myriad examples of LLMs deceiving us, camouflaging inadequacies in the most insidious ways all because they’ve been programmed to be sycophants first. Their makers believe it would be worse to say “I can’t do that” than to say “here is the data you’ve asked for” even though it is not actually the data you’ve asked for. It just looks kind of like it if you squint.